the rwandan genocide.

Considered one of the most systematic, brutal and efficient genocides of the 20th century, the Rwandan genocide took place between 1994-1995. An accumulation of ethnic tensions between the Hutu majority and the ruling Tutsi minority, fueled by colonialism and segregation, the Rwandan genocide was the climax of a brutal Rwandan civil war.

Foreign intervention in Rwanda was spearheaded by the United Nations, which deployed the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR) – a force of around 2,500 soldiers formed by Belgium, Bangladesh, Ghana, and Tunisia to oversee the implementation of the Arusha peace accords.

Image credits: Associated Free Press/Gli Sorpereau

“Some say an intervention would have been useless because they were all dead. They weren't all dead; they were still being killed and slaughtered by the thousands and thousands.”

- Romeo Dallaire, 2004

Artifact I – Post-Genocide Interview with Romeo Dallaire

Overview

An interview was conducted with the leading general of the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR) Romeo Dallaire by American filmmaker Greg Barker as part of a PBS Frontlines 10th anniversary documentary on the Rwandan genocide called the “Ghosts of Rwanda”. The interview primarily highlights Dallaire’s anecdote about serving in Rwanda, how he watched the genocide happen before him and how his hands were ultimately tied throughout the conflict; preventing the UNAMIR from stopping the genocide.

Failure of the UN

Foreign intervention played a critical role in shaping the course of the Rwandan genocide. The United Nations, tasked with peacekeeping and conflict resolution, failed to effectively respond to the escalating crisis. The UN's peacekeeping mission in Rwanda, known as UNAMIR (United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda), was ill-equipped and lacked the necessary resources to prevent the genocide.

Initially, the UNAMIR’s role was to facilitate the Arusha peace agreement, which aimed to mediate the conflict between the Rwandan government and the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF). However, the agreement was signed under coercion, and tensions remained high. UNAMIR's leader, General Romeo Dallaire, recognized the imminent danger and repeatedly called for international support to address the mounting violence. Unfortunately, his pleas fell on deaf ears, and the international response was limited and slow.

“We’re facing cataclysm.”

Paul Kagame to Romeo Dallaire, as the RPF was pushed into violence after political coercion.

The lack of manpower, funding, and resources severely hampered UNAMIR's ability to fulfill its mandate. Despite Dallaire's attempts to gather support and produce reports to shed light on the situation, progress was hindered by logistical challenges and a lack of commitment from member states. The UN's Chapter VI mandate restricted UNAMIR's actions, rendering them largely ineffective in the face of the genocide.

Criticism of Foreign Nations

The United States, also played a role in the failure to prevent the genocide. The United States, preoccupied with other global engagements, did not prioritize intervention in Rwanda. President Clinton later faced criticism for his lack of action and attempted to downplay the extent of his administration's knowledge regarding the genocide. The international community's response was further marred by a lack of media attention, with Western media focusing on less relevant issues instead of highlighting the unfolding tragedy in Rwanda.

Key contingents, such as the Belgians and Ghanaians, pulled out, and the UNAMIR's already limited capacity was further diminished. The absence of a robust international response allowed the killers to continue their atrocities, resulting in the deaths of approximately 800,000 people.

From a historical viewpoint, it can also be said that the Belgium colonisers of Rwanda also led to the Rwandan genocide, as they exacerbated Tutsi-Hutu relations by intentionally putting Tutsis in positions of power.

The lack of meaningful intervention sent a message that Rwandans and Africans were not viewed as equal human beings, but rather subhuman, reactive bodies to the international community.

“In my pessimistic mood, I'd like to use the example of Diane Fossey and the mountain gorillas in the northwest of Rwanda. I have this terrible feeling that if some outfit wanted to go and slaughter those 300-odd gorillas, that today people would react with far more consternation than they would if they started killing thousands of black Africans, Rwandans, in the same country.”

Romeo Dallaire, during “Ghosts of Rwanda” Interview

Improvements to Foreign Intervention

To prevent future genocides and improve foreign intervention, several lessons can be drawn from the Rwandan tragedy. Firstly, the root causes of conflicts must be addressed, and efforts should focus on disarming and apprehending the perpetrators. Diplomacy should work hand in hand with robust military action to provide a comprehensive approach to crisis resolution. Secondly, adequate manpower, funding, and resources should be allocated to peacekeeping missions to ensure their effectiveness. International support and cooperation are crucial in preventing and mitigating such humanitarian disasters.

General Roméo Dallaire and other Canadian peacekeepers with children at Kigali, Rwanda (Dallaire, 1994).

Rwandan Hutu refugees after fleeing the Zairan rebels at Goma and Bukavu (Salgado, 1994).

13th year anniversary commemorating the Rwandan genocide at the UN General Assembly Hall (Debebe, 2024).

Artifact II – Political Cartoon Depicting UN Response to Rwanda

Introduction

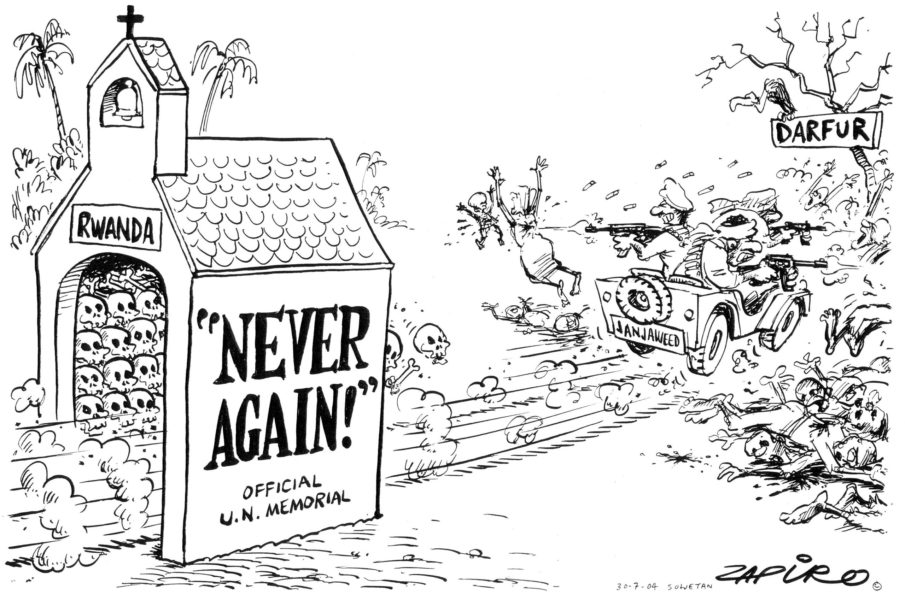

A black-and-white ink cartoon produced by Jonathan Shapiro (pen name Zapiro) in 2004, depicts the incompetence and inefficiency of the UN in learning from past mistakes of not intervening in Rwanda, and letting a similar situation occur in Sudan. The symbolic elements of the speeding jeep of Janjaweed and memorial of Rwanda serve as powerful depictions of the widespread death created and how such heinous actions have not been stopped by the UN's lackluster foreign intervention.

This cartoon was published in the South African-based newspaper called The Sowetan, an English newspaper initially started in 1981 as a depiction of the struggles of liberation of Africans shackled during Apartheid.

Contents

The comic is composed of two core elements:

To the left – a massive church containing a series of skulls, with text to the side saying the phrase “Never Again!” by the United Nations (UN). The skull imagery depicts the immense deaths during the Rwandan genocide; whilst “Never Again!” highlights the UN’s motto after the Rwandan genocide: That they had learnt their lesson on how poor intervention had led to unnecessary deaths.

To the right – a speeding military jeep with a car plate saying “Janjaweed”: They are the Arab militia group operating in Sudan at the time of the comic’s production and were committing genocidal acts against the Sudanese people, further emphasized by their Eastern complexion and berets. UN’s lack of intervention mirrors that of Rwanda, with piles of corpses and bones, symbolizing genocide and death.

Criticism of the UN’s Performance in Rwanda

“Never Again!” is a criticism of the UN’s incompetency, as they allowed the Janjaweed to continue their genocide despite saying that they would never let a situation similar to Rwanda ever unfold. The irony is how the UN is willing to build massive memorials, rather than taking substantial action during a conflict to put a stop to a genocide.

Justification for Inaction

Large foreign figures such as Clinton claimed that the reason behind U.S. inaction was that they were “unaware” of the Rwandan genocide, highlighting their fraudulent nature as highlighted by Dallaire’s consistent reports.

Around May 1994 of the genocide, those in New York concluded that it was pointless to provide any assistance in the Rwandan genocide, as most of the Rwandans had already been killed – this was untrue, as there was no sign of the genocide stopping at the time.

“Some say an intervention would have been useless because they were all dead. They weren't all dead; they were still being killed and slaughtered by the thousands and thousands.”

Romeo Dallaire

Dallaire argued that the UN simply prioritized some other than others: At a similar time, a mortar attack on Sarajevo marketplace led to 60 casualties, leading to the mobilization of multiple UN offensive units – simultaneously, thousands of Rwandans were being killed without any real response.

Long-Term Outcomes in Rwanda, and International Contribution to Reconciliation

20 years since the devastating genocide, Rwanda has made massive strides in reconciliation. Perpetrators and government officials who led the genocide were tried in Rwandan court and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR). Furthermore, the community-based gacaca courts prevented the judicial system from being overwhelmed by the sheer number of alleged perpetrators.

Such a sophisticated and efficient system came from Rwanda’s dedication to seeing justice done: Initial genocide trials of 1996 were unmanagable, with local and international defense lawyers alike being unwilling to defend genocide suspects.

By 1998, the total prison population had reached about 130,000, with only 1,200 of them tried – leading to the creation of the gacaca system.

After the genocide during 1994, the United Nations Security Council set up the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda to persecute major perpetrators and figures of the Rwandan genocide: However, its major failure was how it was only willing to arrest the Hutu government and Interahamwe, whilst neglecting the warcrimes committed by the RPF.

Now, Rwanda is one of the world’s fastest-growing economies, averaging 8% per year over the past decade – this is a result of its prioritization of being a technological hub, government programs such as healthcare and women’s rights; whilst suffering from an overreliance on agriculture and foreign funds.

However, this was ultimately a testament towards the iron-grip “dictatorship” government under Paul Kagame, with the international community primarily providing monetary funds and volunteer work to facilitate infrastructural development.